Taking the class Colonial Africa while exploring Belgium and the Netherlands has allowed me to expand my worldview and learn about the modern legacies of colonialism that form our current global capitalist economy. Since traveling to both Belgium and the Netherlands, it is extremely clear that our current society and economic system is extremely impacted by colonialism. The things that I learned in this class will forever change how I navigate and move through the world.

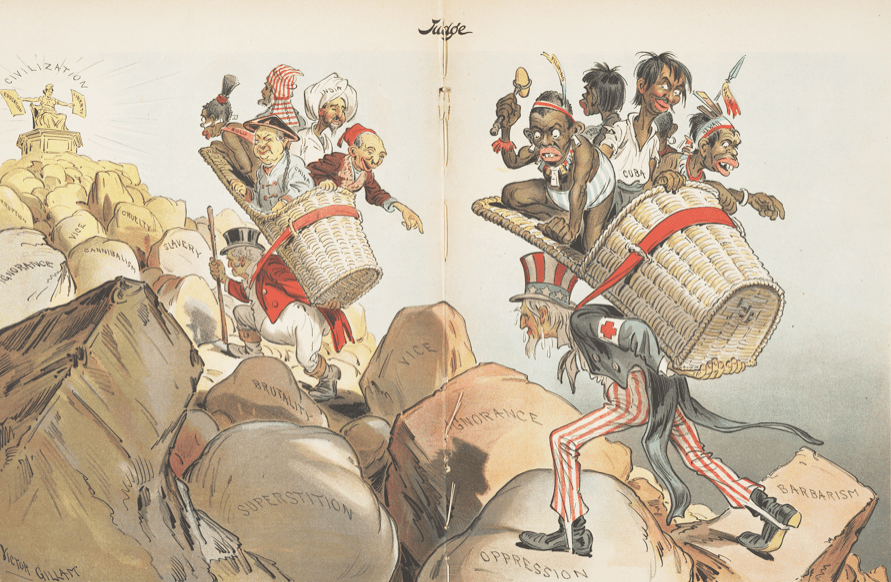

Based on my understanding, the largest repercussion of colonialism comes in the form of historical narratives that are shaped by the use of rhetoric. These narratives then develop into social institutions that form the foundation for a global capitalist system. This might sound extremely confusing and convoluted, however; it’s actually quite simple to understand after learning how important the use of rhetoric was and continues to be in creating ideologies that justify the use of exploitation and dehumanization for financial gain.

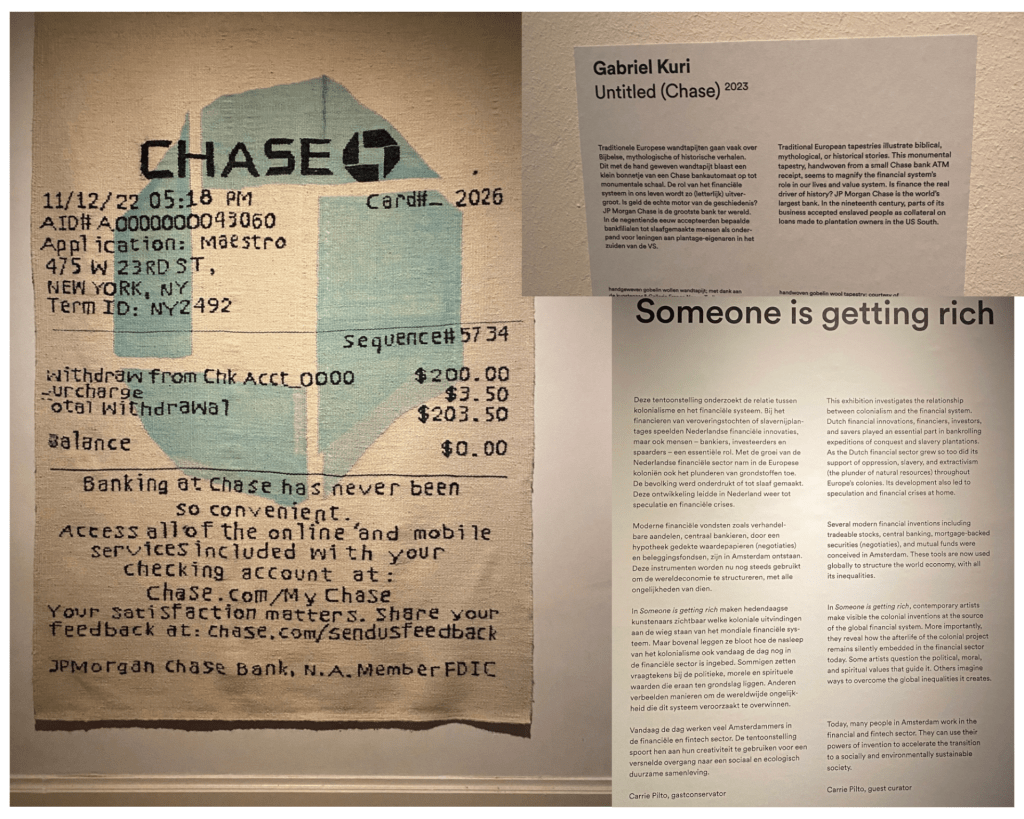

Throughout each of my blog posts, I have discussed the importance of rhetoric and language in not only allowing European imperial powers to deflect responsibility, but also to justify their use of violence and exploitation to reap economic benefits. The use of rhetoric to gain economic control can first be seen by Leopold II and other European imperial powers in the Berlin Conference. During the Berlin Conference in 1885, European imperial powers established a plan to colonize and extract raw materials from Africa.

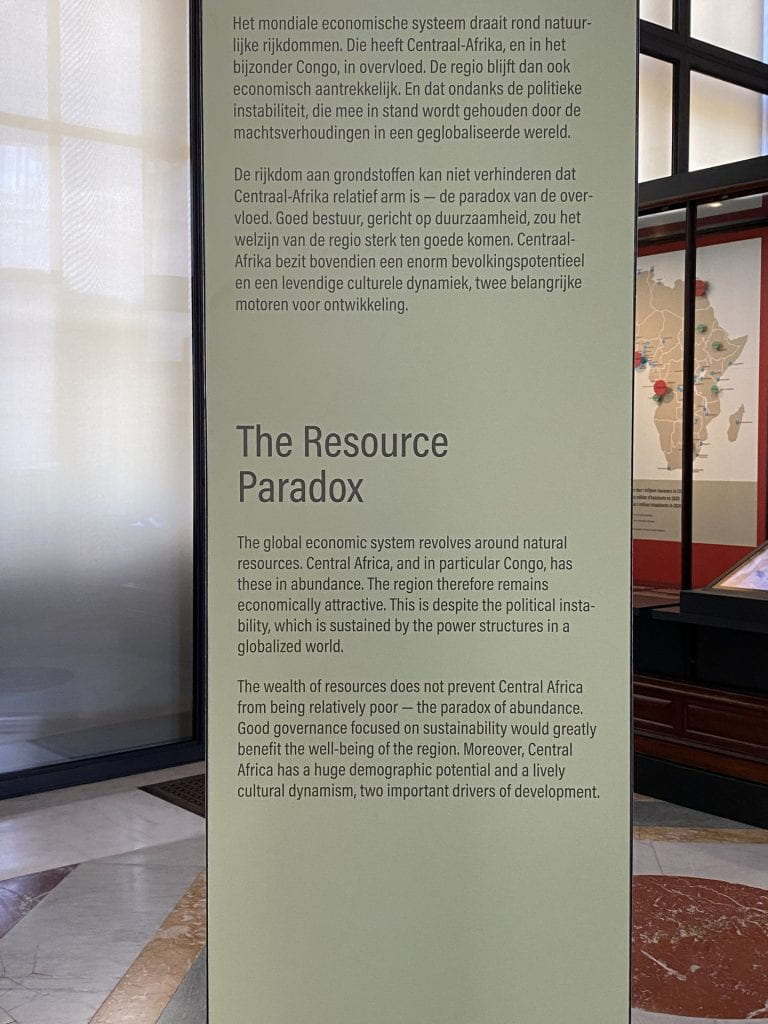

At this point in time, the Industrial Revolution was well underway and the need for raw materials to manufacture and create new infrastructure was higher than ever. Because of this, many European powers looked to Africa for its rich natural resources. Instead of strengthening their trade relationships with Africa in a mutually beneficial way, European powers desired complete control over Africa’s economy and rich natural resources. In order to gain this control, Europeans created an ideology to justify their actions to the general public so they could continue to exploit Africa. This ideology is known as the “civilizing mission,” which painted Africans as inferior, un-advanced and in need of European help to become more socially developed. In actuality, this narrative was created as a propaganda tool to justify the use of violence for economic control. This racist ideology, continues to permeate through our society today in the form of racist stereotypes, racism, and the capitalist standard of beauty.

At the Tropenmuseum in Amsterdam, Netherlands, the exhibition titled “Racism exists, not race” discusses how race is nothing more than a social construction which is used to oppress people and create a social hierarchy. This allows the people at the top to exploit those with less power than them for their own economic gain. This was especially prevalent during the colonial period and can also be seen during during the Apartheid in South Africa. During this period of colonialism, a group of European colonizers settled in South Africa and formed the Afrikaner Nationalist Party. Instead of assimilating into the culture that already existed in South Africa, these Europeans wanted to have complete control over the economy. This meant having complete control over the social institutions that people need to function as a society. The way the Afrikaners seized this control was through segregation, so that people were unable to stand as a united front. This took the form of a series of laws and regulations that made intermingling between races illegal. To put it simply, the Afrikaners were scared that if all of the non-white people were able to stand together, they would overthrow their government and the Afrikaners would no longer reap economic benefits from South Africa’s economy. This example illustrates how historical narratives are used to establish social institutions that enforce economic systems of exploitation.

Another example of the type of economic system that was created during colonialism and continues to be present in Africa today is referred to as the “gatekeeper state.” As Fred Cooper describes in Africa Since 1940: the past of the Present and I mentioned in my previous blog post, the “gatekeeper state” is designed to extract resources from Africa for the benefit of European imperial powers. The economic system set up during colonialism did not disappear after African countries gained their independence from colonial rule. This system continued because during formal colonization, only Europeans were trained as highly-skilled workers that manufactured raw materials and built relationships with trading partners; therefore, even after after Africa gained its independence from colonial rule, it was still dependent upon trading relationships with Europeans to make money from the natural resources that were extracted.

This type of economic system would not have been possible without the use of rhetoric and bogus peace treaties that European powers used to seize control of African countries. Because many Africans did not read, speak, or understand European languages, this allowed European governments to take advantage of and exploit African kings. In addition, European powers wielded their military protection for political and economic control over Africa. If it was not for the use of language to justify, exploit, and take advantage of Africa, our current economic system would not exist.

The most important thing that I learned from this class is that our global capitalist economy is dependant upon dehumanization and commodification to function. This means that our economic system relies on minimizing the worth of people to their rate of output and success. Global capitalism directly relies upon the commodification of all natural resources and the subsequent exploitation of such natural materials to generate wealth. The global climate crisis is a direct result of our globalized capitalist economy which views virtually everything as a means to make money.

In Gregory Claeys’ book, Utopia, he describes the history of liberalism and capitalism. He eloquently explains the reality of our capitalist economy by describing “[i]n its most extreme form, these elements have been conceived as utopian when they are combined in the fantasy of an unregulated market that aims to supersede national sovereignty by a regime of quasi-omnipotent multinational corporations that impose an economic, political and cultural strategy of globalization on the world’s population” (Claeys, 15) He goes onto say that “[l]iberalism has often promised that the good life consisted of maximizing individual liberty, autonomy and independence, and trumpeted the pursuit of greed or selfishness as the means of achieving them” (Claeys, 15).

This brings into question how colonialism has shaped what we value as a society. Based on my understanding of our capitalist system, we value the acquisition of wealth by any means necessary. Often, this means the achievement of wealth through the exploitation of the earth, other people, and ourselves. In Brussels, we saw the reality of this in architecture and statues that were created by leaders as a display of power and wealth. This value system leads to an individualistic culture, which values the self over human connection and the collective. A society which exploits one person exploits everyone. Because we are all human, if we condone the dehumanization of others, we are condoning the dehumanization of ourselves.

Although it is impossible to change the reality of our current economic system quickly, I am committed to making any difference that I can. For me, this looks like taking an internship with the Center for Community, Service, and Justice at my college, having conversations with family and friends about colonialism, and not being afraid to stand up for what I know to be true about the modern legacies of colonialism.

Since taking this class while traveling to Belgium and the Netherlands, I have an exceedingly clear understanding of how vital colonialism was in shaping our current society and economy. Our economy is not sustainable; exploitation is never sustainable. In order to make improvements, we need to see ourselves as a collective. We need to recognize the connection between all of humanity. The only way to begin this change is by examining our past through a critical lens. This will allow us to understand the history of our global capitalist economy and understand what steps need to be taken to decolonize. Learning about our past allows us to see how the ideals, narratives, social institutions, and economies that we have today are influenced by the actions of people that came before us. Without an awareness and understanding of the past, we are powerless to make changes in the present. Since learning about the modern legacies of colonialism, I am committed to the decolonization of my mind, the spaces that I encounter, and the history that I understand.